If you’re in New Zealand and you haven’t heard about the recent shooting in Whangarei, you’re living under a rock (where did you get internet access to read this?). This short article has nothing to do with the specifics of that horrible event and the ongoing investigation – the families of all concerned have been through enough, and there’s plenty of coverage out there if you want more “details” (read: speculation).

Because human beings tend to be macabre and sensationalist, we often focus on the details of how a person committed a crime, or killed other people, before we focus on the “why”. Thankfully, media discourse around the above case has slowly rounded the corner and is now raising questions around mental health treatment availability and suitability. How we as a society treat our most vulnerable is a stark reflection of the state of our country. So far, it’s not a good look.

Should there be a gun register in New Zealand?

When we start talking about murder weapons, satisfying that macabre and sensationalist tendency, people ask the questions – Where did they come from? Should we be able to get these? Could Police have done more? What can we do to prevent this happening again?

I’m going to answer that last question very quickly before diving into the rest; Better equip our mental health services and police force to do their distinct and relative jobs.

So, here is a breakdown of why the registration question comes up:

Media and non-shooters are unaware of what the current gun laws in the country are. Unfortunately, so are many politicians, and even Police who enforce the rules can have a serious shortage of operational knowledge.

Non-shooters are often only exposed to guns in violent media and political discourse from countries such as the USA and the UK – and this forms their perception of guns and how they are used. The reality in NZ is quite different, but unfortunately this is not communicated to them in an accessible manner.

The Police Association (not Police, but the union-type body that represents them) likes the idea of a gun register and strong restrictions on civilian arms ownership – so when they get asked questions by those who don’t understand the law as it stands, the response is often “yes we should register, yes we should ban X type of weapon.” Chris Cahill is the President of the Association, and often its spokeperson. He is also often proven to be generating or referencing false statements, or largely inaccurate numbers, which distort the public view on firearms and legal ownership in NZ.

So, the media asks “Should we register all guns”, the Police Association says “Absolutely”, and Joe Public thinks that that sounds logical, and some very authoritative people have backed up this logical conclusion. So, the purpose of this article, before I get too far off topic, is to introduce the non-shooting, non-hunting public to facts that most shooters are aware of, but which don’t get equal voice in a discussion that would affect the rights and responsibilities of a large swathe of society with, potentially, very little or no upside at all.

Why don’t we register guns in New Zealand?

In the Land of the Long White Cloud, we do things a bit differently. And that’s generally accepted to be a good thing. Kiwis change the world by doing things differently. One thing that we do, which is very different from many countries, is that we “register” or licence the person, not necessarily the firearm.

I personally think this is a great system. In order to legally purchase, own or use a firearm, you must have been vetted by the police and found to be a “fit and proper person” to use an item which is practical, fun and cool, but has serious potential to do harm if in the wrong hands. Your spouse and other referees are consulted by a police vetting officer, and your home and its level of security is signed off as well.

When we make laws that restrict what firearms owners can do, we generally affect those law-abiding people mentioned above. Criminals are not affected by laws targeting firearm licence holders. They’re affected by laws around criminal misuse of guns, and the sentences they get for falling afoul of these rules. Most firearm owners would agree that we need to be much stricter on criminals who offend with firearms, to disincentivise illegally holding weapons, stealing them from people’s homes in the first place, or committing crimes with them. The shooting community would also love to see Police have more resource to solve crimes in which firearms are involved, especially thefts.

But we actually do register guns in New Zealand

New Zealand did have a firearms register a long time ago. Implemented in 1920, after periods of civil unrest and an influx of small arms brought home by soldiers returning from The Great War, a compulsory gun registry, including permits to procure for any firearm sale, was promoted by police and enacted as law. In the early 1980’s, after over six decades of having a gun register, the idea was abandoned, with Police citing an incredible waste of resource in maintaining a database that was increasingly inaccurate. They felt the money and time was better spent promoting other Police activities, and vetting firearms licence holders instead.

“There is no evidence to suggest there is any relationship between the registration of firearms and their control” – NZ Police Support Service Directorate, September 1982.

But, in New Zealand we have maintained registers of a few types of firearm specifically. Pistols, which are held by B-Category endorsed Licence holders, and can only be used at pistol shooting ranges for sporting purposes (i.e. you can’t shoot them on your property, or take them anywhere else, other than a gun shop, gunsmith, or the Police). A pistol licence is incredibly hard to get, and takes around a year – you can read more about the process here.

We also register any C-Category, or “restricted” firearms. These are collectors items, old WWII machine guns, heirlooms, or other fully automatic weapons. These are never, ever, allowed to fired. We also register Military Style Semi Automatic firearms (MSSAs).

We are the only country in the world to follow this last definition, and you need an E-Category endorsement to hold and use one of these. No one else is allowed to even touch the rifle once it is registered to you – even another E-Category endorsed shooter. If you don’t know what an MSSA is, it is basically any semi-automatic rifle that can hold more than 7 rounds in its magazine, or has some other external features, such as a bayonet lug, flash suppressor or pistol grip. An AR-15 (yes, I know you know that one), as standard from the factory in the USA or wherever, would be considered an MSSA. However, New Zealanders can legitimately own one of these rifles for various sporting disciplines (Service Rifle, 3 Gun, IPSC Rifle), pest control (think mobs of goats or wallabies destroying vegetation) or hunting.

If you only hold a basic A-Category licence, you can have a rifle like this, but it must be limited to 7 rounds or less, and cannot have any of the external features that make it look or function like a military weapon.

MSSAs and pistols are what most people think of when they think of gun crime or violent outbursts/mass shootings. These are the most restricted types of firearm in the country, and you have to have increased security measures at your property, go through another vetting process, and you’re subject to police checks annually for pistols, or once every three years for MSSAs. We do register these guns. And there aren’t very many of them actually.

1) Approximately 19,000 pistols held for the purpose of target pistol shooting.

2) Leaving approximately 17,000 pistols possessed for the purpose of collecting, as an heirloom or by museums and theatrical armourers.

3) About 9,700 restricted weapons possessed for the purpose of collecting, as an heirloom or by museums and theatrical armourers.The total number of MSSAs recorded on police systems has risen from the 6,919 reported by Thorp in 1997 to 7,800 – about 80% of this increase of 900 MSSAs recorded is due entirely to the changed understanding (of what constituted a ‘military pattern free standing pistol grip) held by police 9 June 2009 to 1 March 2010. The balance (180 MSSAs) are either ‘walk ins’ (previously unlawfully possessed, ‘off ticket’ but brought within the legal system) or, in the case of about 20, imported on the basis of a special reason not requiring the 1:1 surrender of a worn MSSA.

[E-mail from Inspector Joe Green, NZ Police Licensing and Vetting Manager, 24 May 2010]

Anecdotally, even this tiny database is not consistently maintained. I’m personally a member of many shooters’ forums, and can attest that many shooters of endorsed firearms report that their check-up/review from Police Vetting Officers, included questions about firearms the license holder had never owned, or had sold (and Police administer the sales process of these guns, closely).

Should we register “Sporting Firearms”?

Sporting firearms are the ones you can own on an A-Category licence. They are the most prevalent by far, and include your granddad’s double-barrel shotgun that he used to hunt ducks and rabbits with, the .45 calibre lever action rifle your colleague goes pig hunting with, or the semi-automatic Winchester rifle your neighbour uses to hunt deer once or twice per annum, and paper targets the rest of the year.

By most estimations, there are over a million of these in the country. That’s a big number – should we keep track of these?

Let’s look past the fact that <10,000 MSSAs is a challenging database to maintain, and the fact that a $100 million gun register was rejected soundly in 1999. There are several reasons a register would either not work, or be impossible to maintain.

Police don’t have the resource or capability to enforce

I have four firearms in my safe that belong to another shooter who has an expired licence. Because we are both responsible people, I took possession of these firearms while that person sorts out their licence. I have had these guns for around two years. Police have never asked that shooter what he did with his firearms when his licence expired. When his licence expired, nothing happened.

There is either a lack of capability or resource to enforce on our database of ~250,000 shooters, so how could we manage a register of over a million guns?

Could we register everything out there?

The Thorpe report, which came out in 1997 and is often referred to by the media, points out that less than 90% registration of existing firearm stock would make a register largely useless. If we don’t know how many guns there are, or where they are, or who owns them, how can we ever be sure that we will have registered enough of them to make any sort of difference? How would we even communicate to all of those people who own firearms? Police recently acknowledged that they don’t even know if a firearm owner dies for up to 10 years after the fact (licence renewal period) – so I doubt we’d be able to reach all licence holders within 10 years of any implementation.

And as shown in the example above with my shooter buddy – they still may not find them all and talk to them (and my shooter friend mentioned above lives in Auckland’s Eastern Suburbs – not the side of a mountain on the West Coast).

Can a can register solve crimes?

Proponents for a gun register will posit that once we know where they all are, we can track them and make sure they don’t get into the wrong hands. Assume a 100% uptake of a registry. How are firearms then tracked? It will rely on a purchaser and seller both being honest, law-abiding people who want to follow the rules. Criminals generally don’t fall into this category.

Our current system does have a large component of trust and goodwill between the shooting community (who want to retain their rights – so they tend to behave), and the Police (who have a vested interest in ensuring guns are used appropriately by responsible people). If the new system relies on the same underlying principles of everyone doing what they’re supposed to do, because it’s the right thing to do, I fail to see how we will achieve anything different from the status quo, aside from spending a lot of money.

According to The Star, then Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper said the abolition of their long gun registry, which initially started as recently as 1995, was a major step forward for Canada, in terms of its use of law enforcement resources.

“We simply don’t need another very expensive and not-effective registry,” Harper told reporters Friday near Quebec City. “What we have needed are severe and strong and more effective penalties for people who commit criminal acts using guns.”

Proponents will point out the large reduction of gun crime involving long guns (rifles and shotguns) in Canada since the introduction of the law, but if you look at the trend over time, as shown in the below graph from Statistics Canada, this is part of a larger downward trend, and probably has nothing (or little) to do with the registry, which cost the Canadian government $1.23 billion after deducting licence fees paid by shooters.

Of course, a lot closer to home is the Australian ban/registry/buyback which was implemented by the Howard government after the Port Arthur Massacre. Yesterday I listened to Police Minister and Deputy Prime Minister, Paula Bennett, defend the government’s recent rejection of a $30 million licence system overhaul, a registry and a ban on online gun sales, in an interview with Lisa Owen, on The Nation. When confronted with the inefficiency of a database that would miss “[an estimated] 1.2 million guns that are in the system”, Ms Owen quoted a significant drop in gun-related crime in Australia when our friends across the ditch brought in their gun reforms, including registration. Ms Bennett replied with the fact that in New Zealand, as a percentage of all violent crime, only 1.4% is associated with a firearm – meaning there are much bigger fish to fry, for much more immediate results in saving lives and preventing harm.

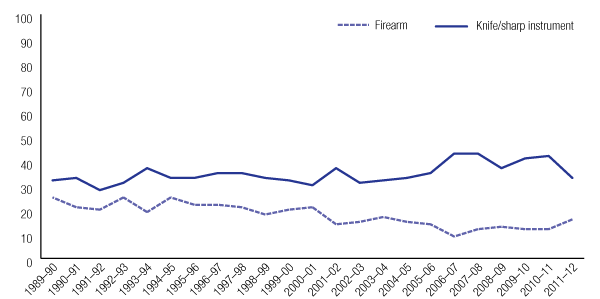

But what about those gun crime stats from Australia? Again, they are part of a longer trend (similar to Canada’s figures for long gun crimes), and affected by much more than a change in laws at a single point in time. The below graph from Australia’s National Homicide Monitoring Program (NHMP) data shows murders and manslaughters on a downward trend since the reforms, but also, despite some spikes, the trend was already heading down.

The below graph, also from the Australian Institute of Criminology’s NHMP, shows guns used in homicides over a longer period of time (since records began), and for context compares to knives and sharp instruments. The trend flattens out a bit as we look at a longer span of time, but the trend is still clearly downward over time, at a similar rate over the series, with the natural exception of some spikes, or “noise” as a statistician would call it.

Of course we can’t just cherry pick data that reflects what we would like to show, and that’s not the point of this article, or this site. If it was proved that a gun register saved lives, this article would have a very different tone – I assure you. So, in the interest of wider context, below are some graphs from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, showing, again, a decline over time in gun-related death in Australia, regardless of the reforms implemented.

Answering the question

So, how many deaths would a gun register prevent? I can’t say that I think it would have a tangible effect in New Zealand at all. Given our low incidence of gun-involved crime, proof of non-performance from overseas gun registers, and unfortunate gaps in Police resource and support, I really don’t believe there would be a difference at all.

My personal opinion is that we could spend the amount a gun register would cost on:

- Educating the public around what the law currently is

- Supporting the police with additional resource to respond to gun crimes with appropriate knowledge and manpower

- Actually solving firearms thefts (they’re already reported – we know when guns are lost, which is the one benefit a register should provide), and;

- Most importantly, giving our country the mental health system it deserves.

Those four areas of concern would do a lot more to reduce gun crimes and deaths in NZ than a database with a bunch of serial numbers in it.