As long as there have been firearms, there have been people trying to improve their performance. Quicker, quieter, lighter, more accurate – these are the motivations of the backyard tinkerer, qualified gunsmith, field armourer and firearms designer alike.

A suppressor, otherwise known as a silencer, sound moderator or sound suppressor, has always been a favoured project for the budget-minded or mechanically curious. One such person recently listed a “V” can suppressor on Trademe, and I couldn’t help but get in touch.

Alan from Hamilton took it upon himself to build a “can suppressor”. The term can suppressor came about as sound moderators tend to look like a beverage can, especially the thicker muzzle-forward variety. This example is literally made from a V can.

The Trademe listing humorously asks;

“Do you want to give your bullets “A guarana and caffeine charged V energy Woo-Hoo”?”

And the answer should be, “Yes, yes I do.”

The tech specs

The top (the end that you drink from) is cut out, and has been replaced with a moulding of ultra high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE). If you just got totally lost, replace UHMWPE with plastic and you’ll get the general idea. This is then drilled and tapped to accept a male 1/2x20UNF thread, the most common thread for rimfire rifles. There’s always the exception, like the Ruger 10/22 anniversary edition, but hey, what can you do?

The other end of the can is a blank canvas, waiting for your first round to punch a perfectly lined-up exit hole. Two things about this. Firstly, it does produce a jagged edge. You could deburr this if you like, but realistically, because it sits below the rim of the can, you probably won’t get your fingers anywhere near it. Secondly, use a subsonic round to do this.

Not only is there less chance of developing too much pressure in the contained environment, but the hollow point should help you create a slightly oversize hole for the following rounds to fit through easily.

The good and the bad

Well, on the positive side, it’s dirt cheap to make if you’ve got the skill. And if Alan chucks a couple more up on Trademe, they are pretty inexpensive to buy – not that economy rimfire suppressors are hard to come by. Also on the plus side of the list is the novelty factor. If we’re honest, everyone’s going to want to check it out and have a go. Lastly, it’s very, very light.

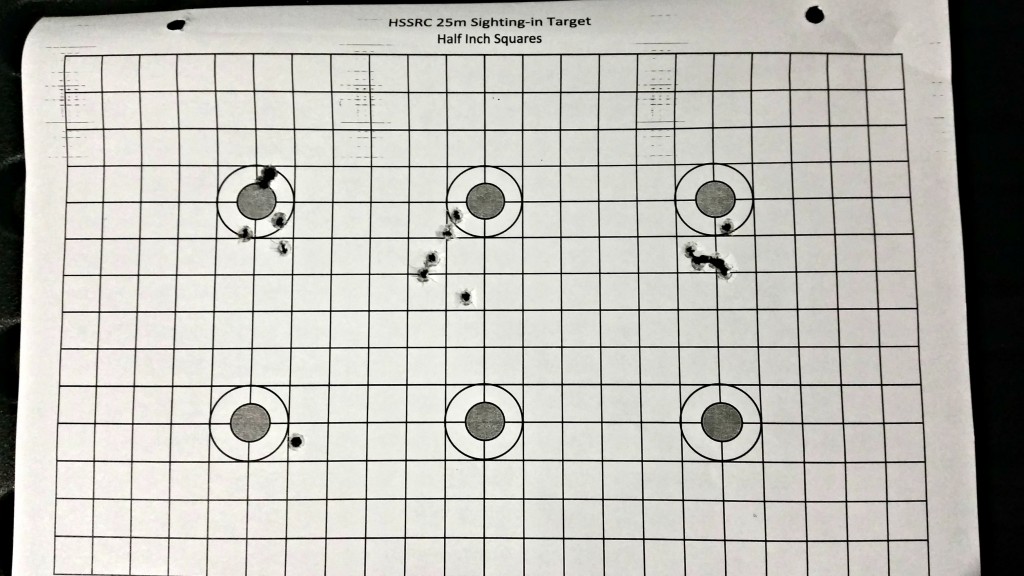

Does it reduce sound? Remarkably – especially when compared to not having a suppressor on at all. In a follow up post, I will do a proper test with a sound meter. The test will be done with two barrel lengths – 16″ and 22.5″ – and with three different sized cans, compared to a regular suppressor and a bare muzzle.

Unfortunately due to technical difficulties, we weren’t able to capture all five rounds I put through the can on video, but we did get the last one. For comparison, listen to how loud it is when I work the bolt afterwards.

On the negative side, you won’t be able to try this trick with a centrefire rifle – you’ll likely end up with a pretty, green mess at the end of the barrel. Also, because this is a relatively simple construction without baffles, the sound is “tinny” – excuse the pun – even if it is reduced.

Of course, being made out of a drink can means that it isn’t the sturdiest object in the world, and if you whack it into a tree or drop it on the ground, you’ll probably end up with a very skew and unusable suppressor. Of course, you didn’t think it was going to be a hardy, hunting-ready solution, did you?

At the end of the day, for a very reasonable cost, you get a novel sound-reduction solution that will help you keep the noise down at the range or in a field full of rabbits or possums. If you do plan on taking it out in the bush, take care of the muzzle end of your rifle – which is much easier with a short or cut-down barrel. For bush use, you should probably think of this as a disposable option. And at such a low cost – why not?