Picking up brass from the range is seen by some to be scavenging, and by others to be a useful service to all range users. But at the end of the day, should you be putting range brass through your rifles?

When you sling a couple hundred rounds down range, chances are you won’t be able to recover all of your brass, especially if you’re shooting a semi-auto rifle. After a shoot we all (hopefully) like to clean up our casings, even if they’re not reloadable. We also pick up our targets and other rubbish because we like to keep the range in good condition for all users – and we like to find it that way too.

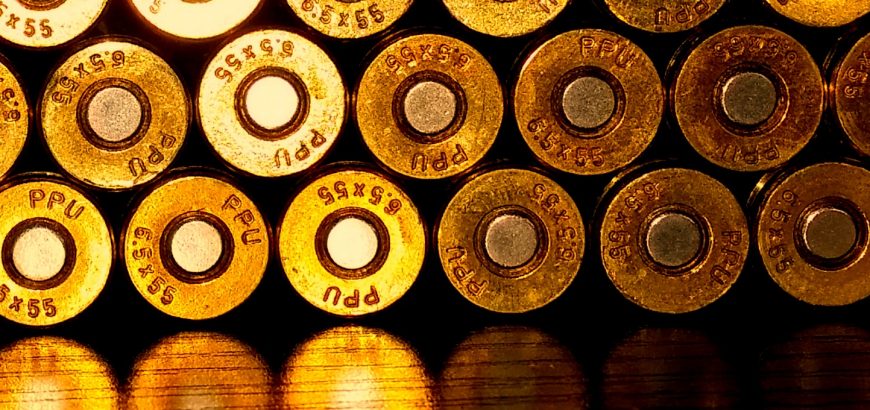

However, while you’re cleaning up and finding (most) of your brass, you come along some shell casings left by other range users. Do you take them? Sure, why not? Picking these up leaves the range cleaner than you found it and probably makes up for some of the brass that you’ve lost. You could recycle it, beef up your collection of weird and wonderful casings, or you could even reload it. But should you?

Reloading casings of unknown origin

When you’re reloading to achieve optimum accuracy, the answer is: No. As mentioned in a previous article, hand loads designed for match performance eliminate as many variables as possible. When you pick up random brass you have no idea how many times it’s been fired, whether it was a factory round or reloaded and what kind of pressures it’s been subjected to.

All of this has a large bearing on tempering and forming of the metal, which ultimately won’t be consistent with any of your own carefully prepared cases. If you’re controlling your shooting and keep brass sorted as unfired, once-fired, twice-fired and so on, why would you introduce a complete unknown into the mix?

Although, we all like to let loose and destroy things from time to time. Not every trip to the range is about absolute accuracy. Sometimes you just want to put big holes in things. Other times you could be introducing your friends to shooting. These are occasions that don’t warrant using your pet loads and favourite materials. In my opinion, range brass is perfect for this.

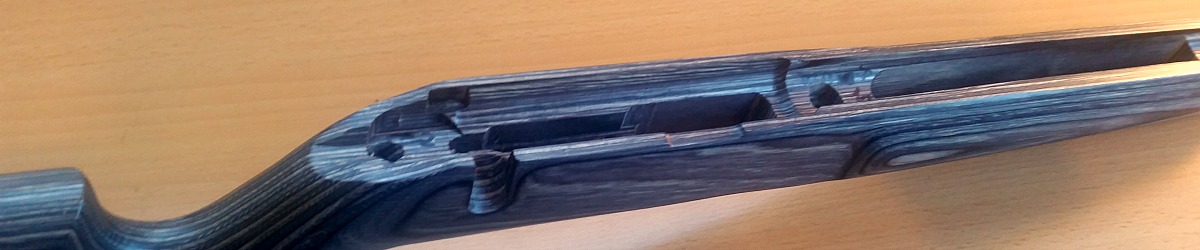

Preparing range brass

When it comes to using unknown brass you’ve got to be more careful than usual – but saving your good brass makes this extra effort worthwhile. I don’t think tumbling is a necessary step in reloading, but when it comes to cases picked up off the range, I think it’s a great idea.

Running your new found cases through a tumbler will remove any unknown dirt or residue that may be lurking around. You should also make sure you clean the primer pocket, trim the case to length and debur/chamfer the inside and outside of the case mouth if necessary.

Remember that these cases may have been fired 6 or 7 times before you ever got your grubby mitts on them, so they could only have one or two shots left in them. But again, remember that you’re saving your good stuff for competition days and hunting trips – when accuracy is really important.

In the meantime, keep your range tidy and your ammo box stocked by cleaning up after yourself and your fellow range users. Just don’t take someone’s brass if they haven’t left yet – chances are they want that when they’re done!