Let me preface this by saying… How long is a piece of string? If you’re looking for the definitive guide on the all-time showdown between factory and custom rifles, you’ve got a long wait ahead of you. There’s no way to say one is categorically better than the other, but depending on your needs, one will suit you more than another. Here’s a quick run down on the two options.

Custom vs “Custom”

Well, maybe there are three options. There are rifles that are custom built by fantastic gunsmiths, or even several different people (i.e. barrel manufacturer, suppressor builder, stock maker, etc), and they can run into the tens-of-thousands of dollars. Chances are you’re not comparing a $35,000 rifle built on a Surgeon action to a Weatherby. So, realistically, these types of custom rifles fall outside of the scope of this discussion.

There are even the customised Remington 700s, Sakos and others you can buy direct from a gun store, which have been assembled with a host of accessories and a non-factory stock, etc, which offer “custom” rifles at lower costs and with a lot less effort. This a kind of middle-ground which, again, falls outside of the debate of custom vs factory.

Factory rifles

There are a host of incredibly good choices out there when it comes to factory target or hunting rifles. And the fact of the matter is, with modern production techniques and better quality control standards, many of these rifles are incredibly accurate out of the box.

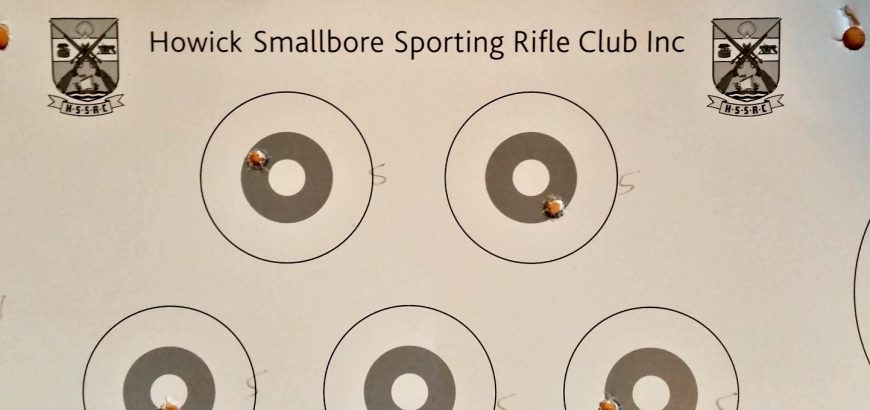

Sako guarantees the Tikka T3 line to produce an MOA 3-shot group out of the box, and they boldly make the same claim with their T3 varmint and tac and 5-shot group. That’s pretty impressive. However, that doesn’t mean your new Tikka T3 Lite in stainless/synthetic will do that with any ammo you feed it. Bear in mind, Sako tests rifles with ammunition they produce themselves.

So, you may need to find just the right brand of ammunition, or even reload your own to get that level of accuracy.

The great thing about factory rifles is that if you look after them and keep track of how many rounds you put through them, you’ll generally get a pretty good resale value if you decide to switch calibres or clean out the safe down the line. Selling firearms is just foreign to me – I want more, not less – so I couldn’t really relate personally. However, for some, it’s a major benefit.

Another aspect of factory rifles, and this is one that I can understand, is that you have warranties and guarantees form manufacturers and retailers. If something goes wrong with a stock-standard rifle, you’re usually okay. Again, this comes down to incredibly efficient modern materials and processes – a lot of manufacturers are so confident, they will give you a lifetime warranty, even with their base models.

Custom rifles

A lot of firearm owners like to try and get more for less. They’ll buy a rusty old milsurp and try restore it, or even convert a P14 action from .303 to a .338 Lapua long-distance shooter. It’s this undeniable urge to make something better and more accurate – but cheap.

Many people try, and many people fail. The old adage “cheap, accurate, reliable – pick two” still stands true. However, not all is lost. Many backyard tinkerers find that they learn more about gunsmithing, rifle maintenance and internal or external ballistics by working on their own firearms than if they bought an out-of-the-box MOA-shooter. It gives you a more holistic view and respect for firearms, and generally makes you a better shooter. The more you know about how your rifle works, the better you can work with it.

What I have found with my own projects, from JW-15s to Swedish Mausers, is you’ll probably spend enough money in the end to have bought a tack-driving factory rifle. So why would you do it?

- The initial outlay is low. Three or four hundred for an M38 in 6.5×55 which might need a lot of work to be great, but at least in the meantime, it’s still good.

- It’s a project. If you yearn to create your own sub-MOA rifle and constantly look up the latest Boyds’ rifle stocks or DPT muzzle devices, then this probably for you.

- It’s unique. Hey, it’s the gun you built, not the one Howa, Marlin or Remington made. There’s a certain amount of pride in this, and you can make it look and feel the way you want.

- Individual needs. Hey, if you need a bush gun – cut down a .303. If you want an odd-looking F-Class gun, try your hand at “improving” an old Mauser. The best part is never feeling bad about cutting into the steel – coz it only cost $250.

Who wins?

Well, if you want a reliable, dependable and accurate rifle to take hunting or to the range, you could go and get yourself a Tikka T3 Lite in stainless/synthetic for less than $1200. Chances are your home-improved P14 or Model 1896 is going to end up costing you more with a new/improved stock, bedding, barrel and chambering, suppressor, bases drilled and tapped, etc, etc.

However, if you want something unique that you can enjoy working on for months – or even years – pick up a donor action to work with. Even an older (pre-1964) M70 or Remmy 700 is fun to use. And the best part is if you buy a complete milsurp, you can probably enjoy shooting it “as is” to start with for very little outlay.

I’ve heard many Tikka T3 owners say their rifle is “boringly accurate”. And that is high praise for any manufacturer. So, at the end of the day, if you want to drill tiny holes into paper or leave gaping exit wounds in deer at 400 yards – get the factory rifle. If you want to feel like you earned your way to shooting sub-MOA or making long-distance kills, a project might be on the cards.